Ukraine

Date: September 2019

Duration: 6 days

Distance: 940km

Leaving Pridnestrovia and crossing the river into Ukraine, I am soon onto a dead-straight road to Оде́са (Odeca). This whole region is flat and geologically very stable, hence the straight roads everywhere. The only thing that isn’t flat is the road surface, which is deeply rutted by all the trucks that drive this route.

This area of the Ukraine is not particularly interesting for motorcyclists, so I will be focusing my attention on the sights along the way. Firstly Odeca.

Odeca is my last visit to the sea-side on this tour. After parking up my bike in a bank’s compound and then changing some money in the same bank, I head out on foot to explore.

Naturally I gravitate to the coastline, strolling through the parks and eventually finding myself with a beer overlooking bathers. I pass the Potemkin Stairs at their base which just as they were designed to do, look huge and foreboding.

From Odeca, I take the motorway north (M-05) in the direction of Київ (Kiev). This is a good quality two-lane motorway. After 150km I turn off it, onto the M-13 – a road that sounds major but it’s broken-up rough concrete and still used as a trunk road.

I am travelling to the Музей ракетних військ стратегічного призначення (Strategic Missile Forces Museum), about 20km north of Первома́йськ (Pervomaisk), and hence why I am riding on what appear to be Ukrainian backrounds. It certainly didn’t help that my SatNav tried to take me across the fields to the rear enterance. It tried to take me, fortunately I was wise enough to stop and adjust the route.

The Strategic Missile Forces Museum used to be a nuclear missile launch site, from which many missiles could be launched at targets in the west. Today it is a museum. On the surface there are numerous items of Soviet military hardware, including helicopters, tanks, MiGs, missile-launching trains, medium-range missiles and one intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

Underground is the real attraction. Through a network of tunnels, one can access the wartime control room located in its own silo below a roof filed with parafin used to hide the control room from remote sensing.

The control column is in the form of a missile. A narrow circular capsule of about 3 metres diameter is suspended in the silo, designed to withstand a direct nuclear impact. This control capsule is about 30 metres in height and all floors can be accessed via the lift, which is itself inside the structure.

The top ten floors are off-limits. According to our guide, the equipment in these levels is considered sensitive, even now.

We take the lift down to the 12th and bottom floor. Here are the crew quarters, where three men would be stationed in the even of a likely war. It is as one can imagine, very crampt.

From the 12th floor we are able to travel to the 11th (from the entry to the structure at the very top, it is only possible to travel to the bottom floor). Here is the war time control room, which is a more claustrophobic version of the peace time control room on the surface. From here it would be possible to execute orders from Moscow. If the Kremlin could not be reached, we were told there were pre-arranged procedures and targets.

Leaving the nuclear missile launch site, the guide asks me where I plan to stay the night. It’s around 5pm, so I need to find accommodation soon. I tell her I’m aiming for the city of Uman, about one hour’s ride away and of notable interest.

Uman is also of notable interest to Jews, and there is a big annual jewish festival. This I already knew about and it’s scheduled for the end of the month, a good couple of weeks away.

The guide informs me that visitors to Uman have been arriving for the past couple weeks. I would be very lucky to find a free room.

Ukraine is very large, the largest country entirely located within Europe, and sparesly populated. If I ride to Uman and there is nowhere to stay, it will take at least another hour to ride somewhere else.

I decide to backtrack to Pervomaisk, 20km south of the museum. For the first time ever I use the hotel search feature of my SatNav (I have no roaming data on my mobile, as I’m outside of the EU).

Within half an hour I’m at a modern looking motel on the outskirts of the city. It’s comfortable but the staff speak absolutely no English. A polish guest helps me decipher the dinner menu.

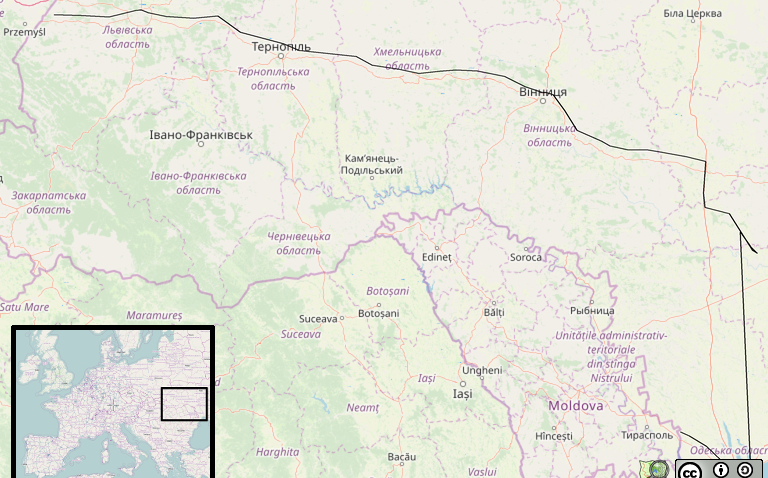

Over the next couple of days my goal is to reach Lviv (Львів), 600km away. There are few other sensible options other than to follow the main trunk roads.

I briefly rejoin the Odesa/Kiev motorway before turning off onto the major east/west highway. The map indicates it is a major highway and so does the volume of trucks, but the quality is more like a poorly maintained country road.

I am faced with the choice of finishing my ride mid-afternoon in Vinnytsia (Ві́нниця) or pushing on to the next city, 1½-2 hours further away. I usually prefer to start my days early, so by mid-afternoon I have had about five hours in the saddle.

I decide to park up in Vinnytsia and book into a fancy hotel for a bargain price. The afternoon is spent relaxing and sight-seeing. I find a small but interesting motor museum nearby.

From Vinnytsia I ride straight to Lviv (Львів), arriving mid-afternoon and checking in to the four star Hotel Dnister for two nights. I plan a day-off in Lviv to be a proper tourist. Unfortunately the secret police museum is closed, but I at least get to see some medieval armour.

Lviv has throughout the past few centuries been part of several countries. It was part of the Habsburg Empire, part of Poland, taken by Russia, then returned to Poland. After Nazi control was ended, the Soviet Union kept it until independence was declared in 1991, just two days after the failed coup in Moscow.

Finally it’s time to return to the EU. Although my goal is in Slovakia, I plan to ride through part of Poland to get there.

Despite the border crossing being low traffic, it takes about 1½ hours to pass through Polish Customs. There were only four cars ahead of me. This is yet another example of tight EU Customs control. The Brits have no idea what they’re in for with their Brexit.

I spend my time in the queue chatting to a couple of Ukrainian bikers. After examining my bike, one of them notices that one of my fork seals is damaged. I suspect the Moldovan and Ukrainian roads may have been a contributing factor.